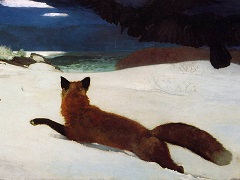

Wreck of the Iron Crown, 1881 by Winslow Homer

The storm pounded in from the North Sea on October 20, 1881, picked up the Iron Crown like a toy and drove the 1,000-ton bark onto the shoals near Tynemouth, on the Northumbrian coast of England. Hundreds of villagers rushed to the Life Brigade House to launch rescue operations.

As night melted into the morning of October 21, members of the life brigade wrestled a boat into the surf and managed to bring 20 people from the Iron Crown to safety. With all but one of the ship's hands accounted for, all eyes turned back to the battered vessel. There the lonely figure of Carl Kopp, a crewman thought to have been washed overboard, appeared on deck, clinging to the ship with one hand and waving with the other. The weary life brigade took up their oars again, plunged back into the sea and brought him ashore.

As this seaside drama rushed toward its denouement, a horse-drawn cab pulled up to the wharf. A dapper little man with perfect posture and a swooping mustache emerged, made his way quietly through the crowd and staked out an observation point overlooking the harbor. Then Winslow Homer produced a pad of paper and a piece of charcoal, sat down and quickly began to sketch salient details of the scene before him: women in shawls leaning into the wind; fishermen in dripping sou'westers scrutinizing the stricken ship; rescuers rowing a lifeboat up through a mountain of water; the Iron Crown wallowing in the distant surf. Homer's view of the ship would be one of the last. Its masts collapsed. It broke into pieces and sank. "Nothing was to be seen of her afterwards," a local newspaper reported, "beyond portions of her stem and stern heaving like black shadows on the water, alternately obliterated by the lashing sea."

Homer disappeared with his sketches, returned to his studio in the fishing village of Cullercoats and set to work immortalizing the life-and-death struggle he had just witnessed. He rendered the scene in a palette of solemn gray, brown and ocher, with raging seas and menacing skies dominating the picture. As he often did, he reduced the subject to a few essentials: gone were the men and women he had sketched on shore; gone was the sturdy stone wharf underfoot; gone was any reference to land at all. Homer plunged the viewer right into the churning sea, along with the tiny humans struggling against it. What is remarkable is that he chose to produce The Wreck of the Iron Crown in watercolor, a delicate medium then generally considered to be the weapon of choice for amateur artists, at least in Homer's native America. But he seldom played by the rules.

Age 45 when he appeared in Cullercoats, Homer was already recognized for his achievements at home, but he was clearly eager to improve his artistic reach. Most likely, he went abroad to escape the social distractions of New York City, to search for fresh subjects and to explore new ways of presenting them. This is pure speculation because the sometimes reclusive Homer was notoriously unrevealing about his personal affairs, his methods of painting and his artistic intentions. "Mind your own business!" were his four favorite words.